The Florida Project: What's wrong with this picture?

On the challenges of the present and the power of the past

Last night was movie night with our friends, “Lauren and Eric.” The four of us (including my wife) usually get together on Sundays around 7pm, eat dinner (this time we got takeout — felafel and assorted salads, plus wine and hard ciders), and then we scroll through the streaming services, looking for a good movie to watch. Last night’s pick: The Florida Project, a story about…

… the vibrant, unchaperoned summer of six-year-old Moonee and her friends, who live with their struggling single mothers in a budget motel near Disney World. While the children find wonder in their transient surroundings, the film poignantly reveals the harsh realities of their mothers’ daily battle with poverty. It’s a stark yet tender portrayal of childhood innocence juxtaposed against profound economic hardship, leading to a heartbreaking climax.

Shorter version (no ChatGPT): The Florida Project is about losing almost everything and everyone — money, housing, food, family, friends, spouses, community, justice, hope, and love — leaving you at the edge of a cliff, staring into the abyss. It’s terrifying.

After the movie, we talked about the story and tried to answer some questions, which fell into two broad categories:

The Challenges of Right Now: Why did Moonee and her friends intentionally burn down the vacant house? Why didn’t Moonee’s mom, Halley, provide more guidance and structure for her daughter? Is it okay to steal food so you can feed your children? Is there a problem with earning a living as a prostitute? Are there ways to improve the laws and regulations that govern sex work? What about a guaranteed basic income? Could that be a solution? Or maybe subsidized food and housing, which would provide an immediate boost to their standard of living. Should Halley and Moonee leave Florida and move to New York City, where Mayor Zohran Mamdani might offer them rent-controlled apartments and inexpensive food from municipally-run grocery stores? (There’s lots of grist here for the public policy mill.)

The Power of the Past (or: Show Me The Prequel): How and why did Halley and Moonee arrive at this dead end? Where is Moonee’s father? What was Halley’s childhood like? What lessons did her parents teach her? Was she told that All Roads Are Good? Or that Some Roads Are Bad?1 Do you need a positive vision for your future to give purpose and energy to your present and meaning to your past? Can we effectively deal with a crisis by considering only what we see in front of us right now? Or do the variables that shape our lives exert their influence over time, long before the crisis erupts? When creating a portrait of a person, a family, or a nation, how wide or narrow should we set our field of view?

While both approaches are essential if we hope to understand people and their lives, I lean toward the second one — the Power of the Past. The wide-angle POV, which includes the characters’ essential backstories, often tells me more than zooming in for a close-up. History matters.

The story of Gaza: Zoom in or zoom out?

The world is transfixed right now by close-ups of Gaza — an endless digital stream of destruction, suffering, and death, prompting good people of goodwill to ask: Why doesn’t Israel stop the killing?

But when the Israelis zoom out to explain exactly what’s happening and why, most people become confused. Or bored. Or they’re simply not interested. The history of the region is complex and presents all sorts of maddening contradictions. How can Israel remain both a Jewish state and a democracy? Why was the PLO founded in 1964 when Palestinian Arabs already controlled the West Bank and Gaza? What land was the PLO planning to liberate? Isn’t there a way to destroy Hamas without killing innocent people? And why should we destroy Hamas, anyway? Aren’t they a liberation movement? What is a Palestinian? And what land is “occupied,” exactly?

There’s too much to process, so lots of people fall back on a simple answer: Killing is bad. Stop the killing.

Then, when Jews suggest zooming all the way out to tell the 3,000-year-old Story that explains how we all got into this predicament, some folks lose their temper. Enough! they scream. Stop yapping about yourselves! Can’t you see Israelis are killing innocent Palestinians right in front of your eyes? Are you blind? Or are you Jews just narcissistic, blood-thirsty monsters?

Gaming the system

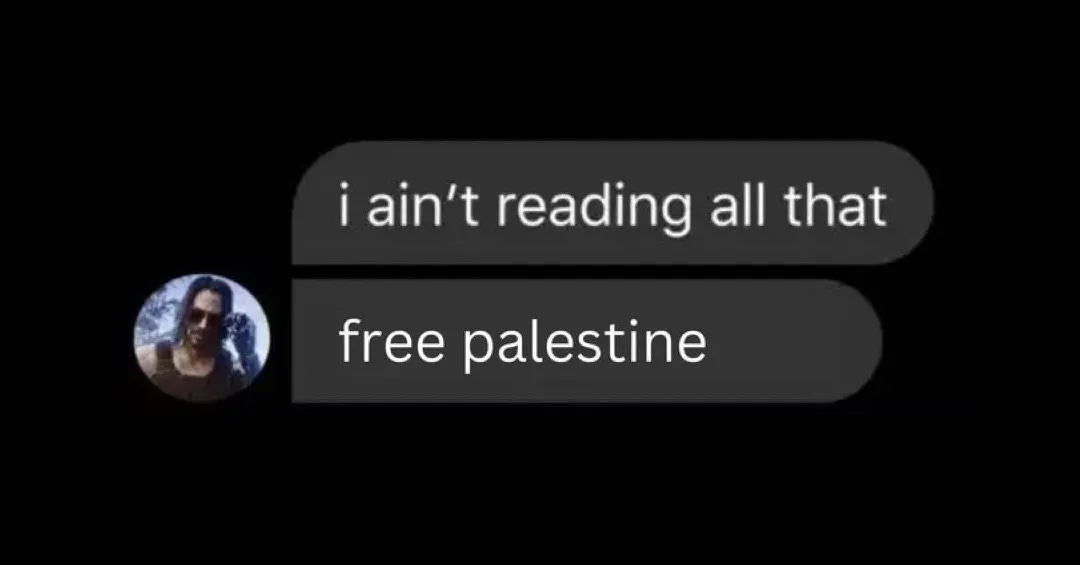

Hamas and the Iranian mullahs understand all this, of course. They know us better than we know ourselves. They know we have no attention span and no memory, and that we become transfixed by whatever is in front of us right now. They know the horror of October 7th will be forgotten by November 1st. They know we get bored easily and need to keep scrolling. They know we love pictures and hate to read. In short, they know we are all Trump.

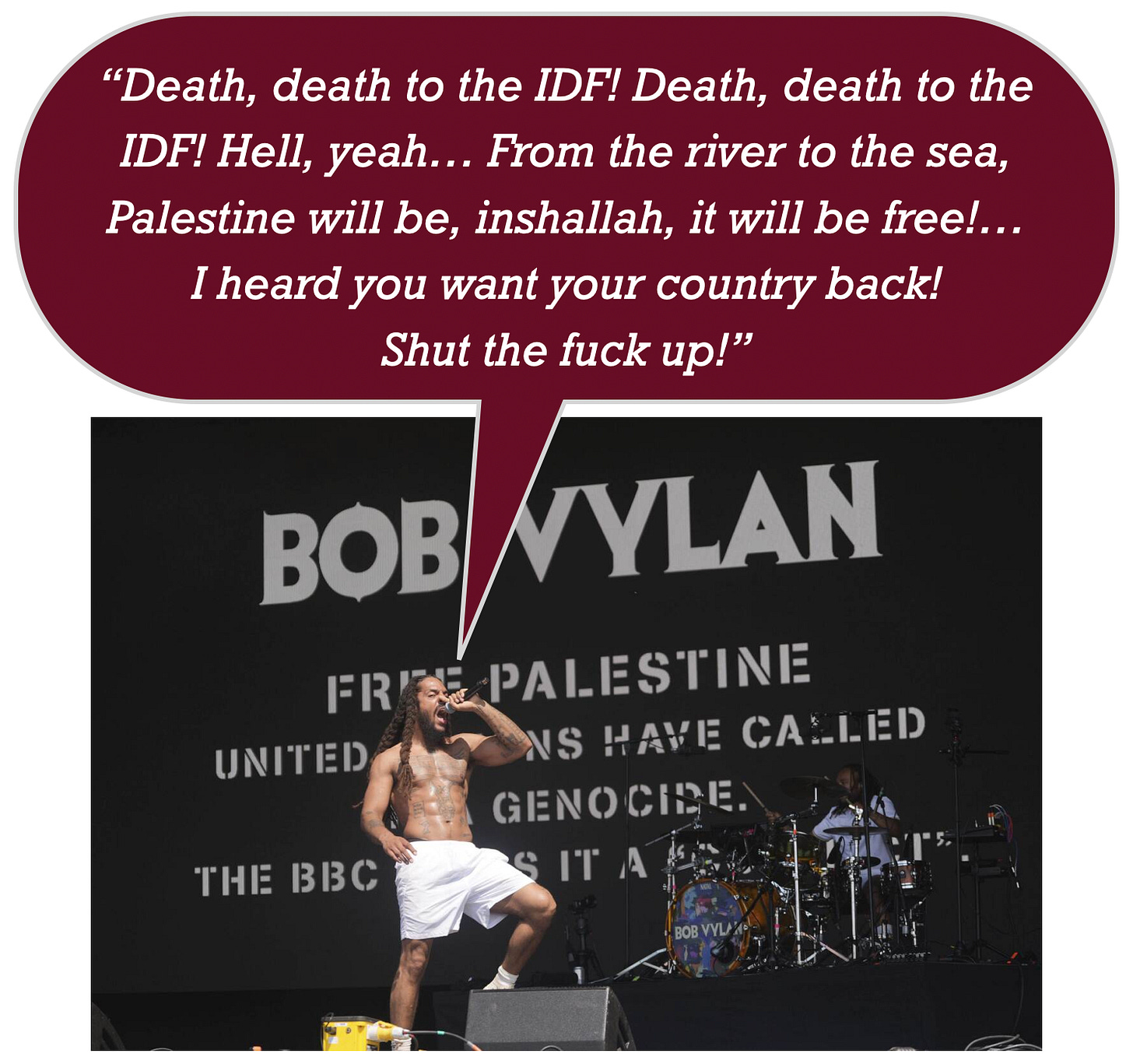

The Islamists are different. They have a Story that goes back 1,400 years, and a long memory rooted in the Quran. Peek inside their heads and you’ll see a movie playing — call it Mohammed: Days of Reckoning, Days of Rage — in which they have cast themselves as the heroes. It’s an epic, swashbuckling adventure in which Islamists save the entire world from degeneracy, avarice, sin, and the grave theological errors committed by Jews and Christians. (Distribution of the movie is expanding rapidly, which means it should be coming soon to a theater near you.)

No wonder the streets of Europe and North America now echo with catch phrases from that movie: Free Palestine! From the river to the sea! Zionism is racism! Death, death to the IDF!

I hear these chants day after day, and it makes me dizzy. It’s as if I’m standing on the edge of a cliff, staring into an abyss of lies, hatred, ignorance, and darkness. Yes, it’s terrifying, but it certainly isn’t new.

Zooming way, way out for a glimmer of hope…

Today on Substack, Daniel Saunders wrote:

I was thinking recently that it isn’t enough to inculcate values. If we want to rebuild Western society, we need to revive the ancient stories that embodied those values and through which we learn them.

I’ve been thinking the same thing for 40 years, so allow me to second Daniel’s motion.

One place to begin might be the Tower of Babel.

The tagline for The Florida Project is Find Your Kingdom. Problem is, the kingdom that Moonee eventually discovers is another dead end.

I grew up on Hebrew Bible stories. They shaped me way more than the New Testament. Way more.