I. Toeing the party line

It’s 2004, and I’m meeting with one of my editors at National Geographic magazine. Let’s call her “Susan.”

We’re sitting in her big window office, making the final tweaks on some photo captions I’d written for an upcoming feature story. When we finish, we chat for a while — about the recent staff meeting with the National Geographic Society’s CEO… about the Magazine’s expanding international partnerships… about some recently approved feature stories… and about our families and mutual friends.

Then, as I get up to leave, I see a poster that’s been hanging on the wall of Susan’s office for years:

“I hope you don’t mind if I ask you this,” I say, pointing to the poster, “but do you really believe that tagline — that ‘All Roads Are Good’?”

Susan pauses for a moment, then smiles a bit sheepishly.

“No,” she says. “Not really.”

“Yeah,” I say. “Neither do I.”

II. As National Geographic goes, so goes America

In 2008, the Editor-in-Chief of National Geographic fired me. I was among dozens of Magazine staffers who were sacked in a series of downsizings that had begun at least a decade earlier and continued for more than a decade after my exit.

On my last day at the office, I stopped at the National Geographic Society (NGS) gift shop, where I paid $19 to become an official Society member. (The Magazine has long been “the official journal of the National Geographic Society,” so most people who read the Magazine are not subscribers; they are Society members.)

A few months later, I launched an online project called Society Matters, which explored the past, present, and a possible future of NGS. I ran this (after-hours) website for almost five years, at which point John Fahey, who was then the Society’s CEO, lost patience with my unsolicited and public editorializing about his decisions and leadership.1 As a result, John dispatched his lawyers, who “persuaded” me to shut down the site… but that’s another story for another day.2

The story I want to share now is a very brief history of National Geographic magazine itself. This 137-year-long narrative, condensed below into a three-act drama, reveals who we Americans once were and what we have become. It goes something like this:3

Act I: Follow The Science (1888 to 1941)

Launched during the Progressive Era — a time when Americans had seemingly unbounded faith in their power to solve the world’s problems — National Geographic magazine focused primarily on science and physical geography. For 53 years, the Magazine explored the far corners of the world, embraced the scientific method, avoided moralizing, developed its groundbreaking photojournal(ism), endorsed the eugenics movement, and published painfully racist stories and flattering portraits of fascists.

For example, in February 1937, National Geographic published “Changing Berlin,” a 47-page feature story by Douglas Chandler. According to Bob Poole, a former NGM editor and the author of Explorers House: National Geographic and the World It Made, Chandler…

Here’s my vision of Hitler getting briefed on Chandler’s story, just as National Geographic was beginning to change its editorial course:

One month after NGM’s story about Hitler’s Berlin, the Magazine published a glowing overview of Mussolini’s Rome (March 1937).

Race theory, scientism, unbridled nationalism, and fascism — they seemed like a good idea at the time.

Act II: NGM’s Big Pivot — America & the West Greet The World (1941 to 1996)

After Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of World War II, the Magazine woke up and made a 180-degree editorial pivot. The editors promoted the sale of U.S. war bonds on NGM’s cover to help fight fascism. They gave maps to Gen. Eisenhower to help Allied forces defeat the Nazis. They told stories about brave American troops stationed in Korea. And they spent most of the next 50+ years narrating the liberal democratic adventure for an English-speaking audience with stories like America Through Lincoln’s Eyes and Thomas Jefferson: Architect of Freedom.

NGM also published beautiful single-topic issues to celebrate the bicentennials of Australia (1988) and France (1989) because those two countries shared a political narrative animated by the same Enlightenment values that we Americans embrace. The Magazine also covered the massacre of democracy activists in China’s Tiananmen Square. However, NGM did not publish any stories about the Soviet Union because the editors were staunch anti-communists.

If National Geographic magazine had an unofficial tagline in those years, it was: America & the West Greet The World. Curious about all lands and peoples, NGM also had a clear understanding of who we were and were not. The Magazine discriminated in the best sense of the word. It drew distinctions. It noticed differences. Readers could learn about people in other cultures without adopting their values as our own: In some places, women walk around with bare breasts, but in the West, women cover up. Isn’t that fascinating!

In this second editorial incarnation, the Magazine was a huge success, partly because the editors understood that some roads are not good. By the 1980s, with more than 10 million people paying annual membership dues, money poured in much faster than the Society could spend it. This was National Geographic’s Golden Age.

Act III: International Geographic (1996 to present)

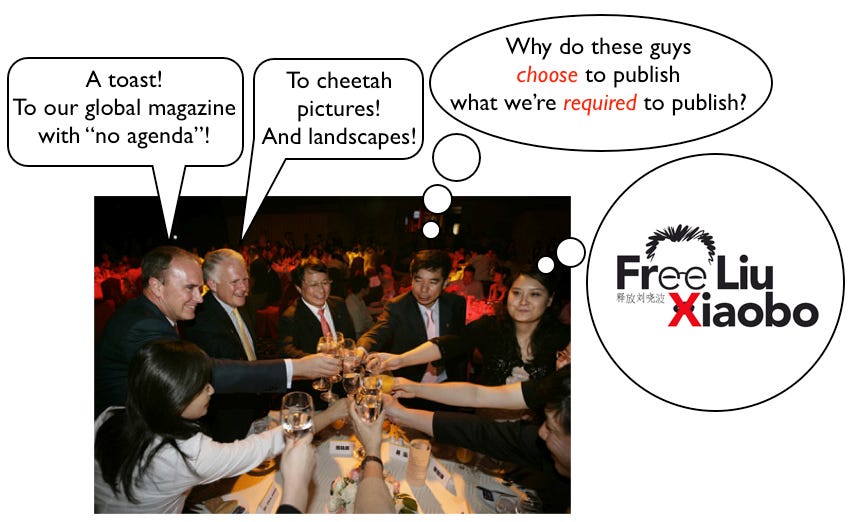

After the fall of the Soviet Union, and with (former) CEO John Fahey at the helm, the Society set out to become a global media company. But to do business in China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and many other countries that are hostile to democratic values, the Magazine had to execute another 180-degree pivot — back to science reporting with lots of stories about climate change and cheetahs and beautiful landscapes. That meant no more celebrations of Thomas Jefferson or James Madison or Abraham Lincoln. In exchange for abandoning The Democracy Story and embracing The Planet, National Geographic was given the world. Today the Magazine is published in more than 30 different “local-language editions.”

Here is John Fahey describing the Society’s new mission statement — “to inspire people to care about the planet” — which found an enthusiastic audience in Beijing, Riyadh, and Moscow:

Once again, the Magazine is a publication that even authoritarian thugs can enjoy, which suggests that whatever lesson the Society learned in 1941 seems to have been (intentionally) forgotten.4

III. All roads are not good

As National Geographic went global and launched its many international editions, the Society’s executives traveled the world to promote the new Magazine by piggybacking on the warm feelings people had about the old Magazine.

This tension between what National Geographic was and what it has become is glaringly obvious in the video below. It features then-Editor-in-Chief Chris Johns and NGS corporate counsel Terry Adamson talking with a very perceptive Russian TV host. Listen for Terry’s begrudging admission about NGM’s editorial point of view “20, 30 years ago,” and how that contradicts Chris Johns’ insistence that NGM was “objective” and never had an editorial agenda or political point of view.

If you sometimes get the haunting feeling that the story of America and the West is vanishing, you shouldn’t be entirely surprised. National Geographic — which once was among the most popular and beloved magazines in the English-speaking world — abandoned that story “20, 30 years ago” by insisting that “all roads are good.”

They are not. And believing they are can take us to a dangerously dark place.

My Google Analytics dashboard indicated that I was getting a lot of web traffic from inside of NGS headquarters. I was also told by an insider that some of my Society Matters reporting was popping up during meetings of the Society’s Executive Management Council. This, I think, is why the Society’s lawyers started sending me not-so-friendly letters.

I mothballed the Society Matters website a few years ago, but you can still find remnants in the Wayback Machine.

I shared a shorter version of this history last year (“Are you a citizen? or a customer?”), but I like to think this post is making a different point.

In 2015, the Magazine and all the Society’s other media properties were sold to Rupert Murdoch’s 21st Century Fox. And in 2019, Murdoch sold it all to Disney.

"Readers could learn about other cultures without making their values our own." Alan, you just summed up the opposite of this moment in history, where so many embrace other cultures as their own and adopt their jihadism as both a moral necessity and cultural norm. That Mamdani just won the Dem vote in NYC while protesters march in support of Iran while condemning Israel and Jews feels historic to me and this article helped me understand some of why I feel this way. Love your storytelling even if the moral of this story describes today's moral compass spinning wildly out of control. And the part about the meerkats in the Hitler video just killed! I could not stop laughing. Brilliant and funny. Thanks for another gem and for fighting the good fight and outing the NGS. So well done!

This was very educational! I had no idea. When I was a kid in the 70s and 80s my mom subscribed to the magazine. By the 90s my mom had died but dad kept renewing it in her name. At one point he cancelled. I think now I know why….