My interview with Ludwig Von Mises (1881 - 1973)

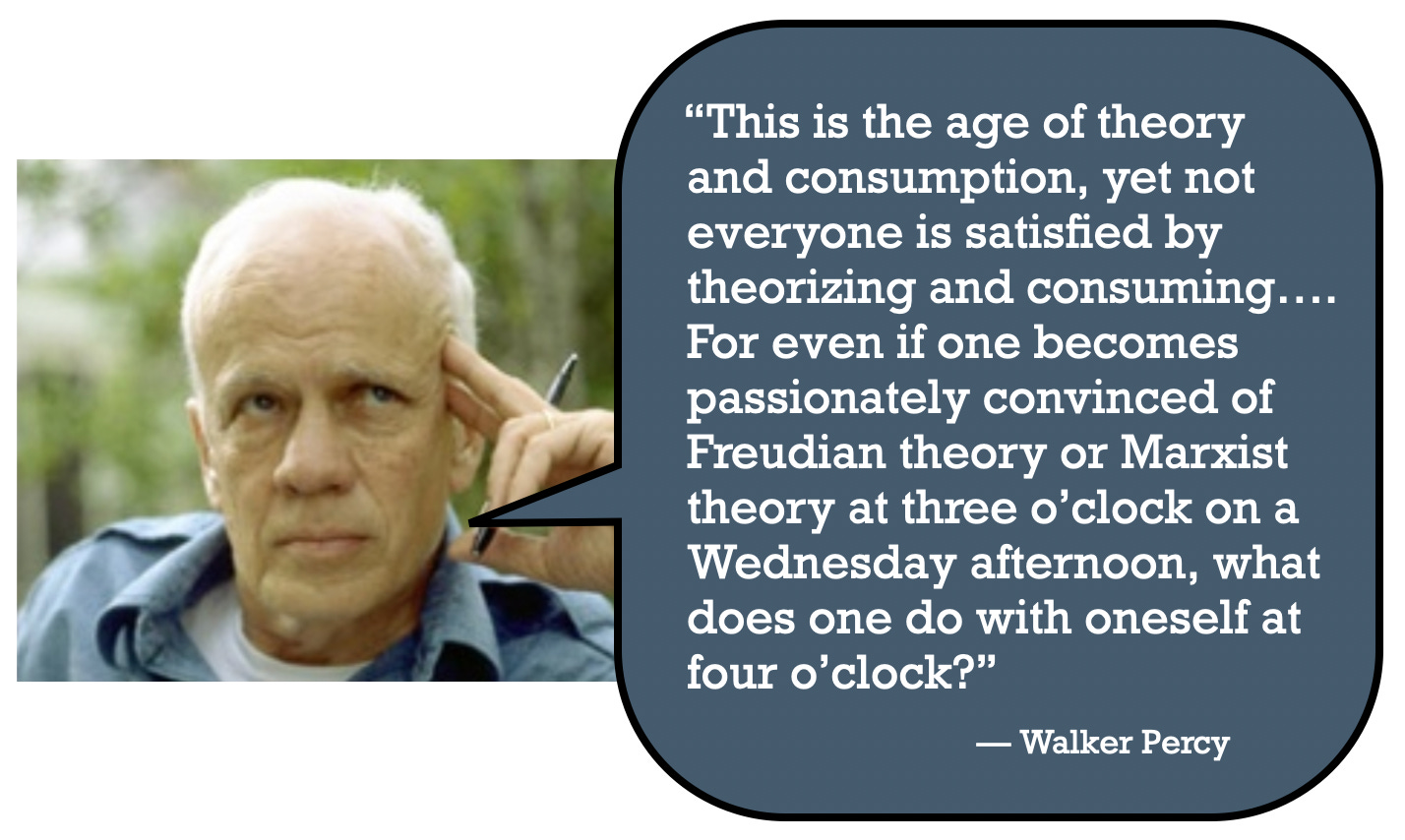

The danger of Theory and the possibility of Story

Ludwig von Mises was a leading Austrian-American economist and philosopher of the 20th century. A central figure of the Austrian School of Economics, he advocated for classical liberalism and a free-market system while offering powerful critiques of socialism.

Alan: I’ve heard your name for years, but not until

posted an excerpt from your book did I actually read anything you’ve written.Ludwig Von Mises: Daniel is a good man. More people should subscribe to his Substack. But what took you so long to discover my work? Didn’t you major in economics?

Alan: I did. And you’re right, I should be more familiar with your work. But your name — Ludwig Von Mises — it’s funny, so maybe I had a hard time taking you seriously. Thanks to Daniel, I now see what I missed. And thank you for returning from the dead for this interview.

Ludwig: My days are quiet now, so talking with you is a rare pleasure.

“Beware of the experts!” said the expert. (🤦♂️)

Alan: If I had to summarize the excerpt that Daniel shared, I’d put it this way: For democracy to survive, citizens must not surrender their sovereignty to experts (i.e., government bureaucrats) but instead actively engage with fundamental economic principles. Is that fair?

Ludwig: Yes.

Alan: What makes you think people have time to “actively engage with fundamental economic principles”? And what’s fundamental? Fundamental to you? Or to the average guy on the street?

Ludwig: “Fundamental” as in basic. The core building blocks. The essential theories and mechanics of economics.

Alan: Hmmm… that doesn’t really make sense.

Ludwig: Why not?

Alan: As a citizen, I can learn about fiscal policy, which is basic, but the bureaucrat, who is a specialist, an expert, can dismiss me because I don’t know enough about monetary policy. I can then learn about monetary policy, also basic, but the bureaucrat can dismiss me because I don’t know enough about seigniorage. I can learn about seigniorage, but the bureaucrat can dismiss me because I don’t know enough about special drawing rights. I can learn about special drawing rights, but the bureaucrat can dismiss me because I don’t know enough about Treasury auction tail. On and on it goes.

This is a losing game for the average citizen because “basic” is never enough, especially when dealing with the “experts.”

Ludwig: It’s only a losing game if you refuse to do the hard work of citizenship. Democracy takes effort, son. You need to do the assigned reading.

Alan: No, you don’t understand. You think the world is like a college campus because academia is the world you know best. You sit in your ivory tower thinking deep thoughts and chatting about them with other deep thinkers, and you devise all sorts of theories about the way the world presumably works. Well, bad news, my friend: the world is not a function of what you think. The world is not Theory. It exists independently of whatever you might imagine.

Ludwig: That’s a bit harsh, don’t you think? Ideas matter. Rigorous thinking and good ideas produce wise actions.

Alan: Yes, thinking matters. Ideas matter. But while you think deeply and develop new theories about how the world presumably works, the plumber is fixing pipes, the baker is kneading bread, and the electrician is replacing faulty wiring. They work all day, come home, eat dinner, spend some time with family, help junior with his math homework, check the box score of the Red Sox game, watch a rerun of “Three’s Company,” and hit the sack. These people are what we called, during the Covid shutdowns, “essential workers.” They have no time to read your Human Action: A Treatise on Economics, or to learn about “praxeology” and your defense of free-market economics.

Ludwig: Their loss, I’m afraid. I write about what we call “essential ideas,” and if we don’t absorb them, we shall fall prey to charlatans peddling fairy tales about central planning and socialism. I’m thinking here of guys like Zohran Mamdani. But hey — ignore my warnings at your peril.

Alan: That’s not my point. Your criticisms of socialism are probably accurate, and Mamdani is a potential disaster for reasons that extend far beyond economics. But to suggest that democracy requires that everyone must be familiar with the language you speak is absurd. Not only that, the system you champion — free-market economics — is all the evidence I need to prove that you, sir, are playing a shell game.

Ludwig: What do you mean?

"Step right up, folks, and try to follow the pea!"

Alan: Let’s review the basic assumptions of economics. People are autonomous actors. Their decisions are driven by self-interest. By pursuing their self-interest in a competitive market, we can achieve a Pareto optimal distribution of goods and services while avoiding the corruption and depredations that often accompany economies centralized around state power and planning. Fair?

Ludwig: So far, yes.

Alan: And you — you’re an actor in this marketplace, are you not? You are stuck in this competitive, material world just like the rest of us normies. You’re not somehow magically suspended above us, looking down, just because you teach at a university. You’re subject to all the same assumptions about self-interest that apply to all incarnations of Homo economicus. You, too, are an individual who, in the words of your theory of praxeology, “acts purposefully to achieve goals.” Correct?

Ludwig: Correct.

Alan: Now, think about your goals and your competitive advantage. You’re a smart guy, Ludwig. You know stuff that other people do not. Students pay good money to attend the university, sit at your knee, and learn the gospel of Praxeology. Right?

Ludwig: Right.

Alan: But once they’ve learned what you have to offer, your competitive advantage has diminished. You’ve shared your intellectual goods in an economic transaction — knowledge for money — which leaves you marginally less wise than your customers.

Ludwig: When I teach, the knowledge gap between me and my students closes a bit, yes. That’s the purpose of education. But that gap soon widens again because the frontier of knowledge is constantly expanding. What we know today is merely a whisper of what’s to come.

Alan: Exactly right. So you return to your office and weave together another theory, book, or abstract construct. Or in economic terms: Supply creates its own demand, especially when juiced with effective advertising: “What you earn is a function of what you learn, so go to college!” Your challenge, as an economic actor, is to maintain the supply. To keep generating new ideas. And look at how good you are at this game! Here are some of the products of your extraordinarily fertile mind:

The Theory of Money and Credit (1912, enlarged US edition 1953)

Nation, State, and Economy (1919)

Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis (1922, 1932)

Liberalism: In the Classical Tradition (1927, 1962)

A Critique of Interventionism (1929) (collection of essays)

Epistemological Problems of Economics (1933, 1960)

Interventionism: An Economic Analysis (1941, 1998)

Omnipotent Government: The Rise of Total State and Total War (1944)

Bureaucracy (1944, 1962)

Planned Chaos (1947, added to 1951 edition of Socialism)

Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (1949, 1963, 1966, 1996)

Planning for Freedom (1952, enlarged editions in 1962, 1974, and 1980)

Theory and History: An Interpretation of Social and Economic Evolution (1957)

The Ultimate Foundation of Economic Science (1962)

The Historical Setting of the Austrian School of Economics (1969) (long-form essay)

Notes and Recollections (1978, written in 1940–41)

On the Manipulation of Money and Credit (1978).

Economic Policy: Thoughts for Today and Tomorrow (1979, collection of lectures given in 1959)

Money, Method, and the Market Process (1990) (collection of essays)

Economic Freedom and Interventionism (1990) (collection of essays and addresses)

The Free Market and Its Enemies (2004, collection of lectures given in 1951)

Marxism Unmasked: From Delusion to Destruction (2006, collection of lectures given in 1952)

Ludwig von Mises on Money and Inflation (2010, collection of lectures given in the 1960s)

Ludwig: Pretty impressive, don’t you think?

Alan: I do! But here’s the thing: Imagine you’re an economics student in 1800. The syllabus is rather limited because the discipline is new, so you can learn the basics in relatively short order. But 225 years later, the economics discipline has grown into something maddeningly complex.

Put another way: In 1800, economics wasn’t yet the distinct, specialized field we know today. It was primarily a branch of moral philosophy known as political economy. The core areas of study were the theory of value and distribution, economic growth and development, monetary theory, and international trade.

Ludwig: All essential.

Alan: Yes, but economics today is much more specialized, with countless sub-disciplines that have emerged from the basic framework of classical political economy. Here are just five arcane corners of modern economic thought that are intelligible only to experts like you:

Microfoundations of Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium

Econometrics of High-Frequency Financial Data with Jump-Diffusions

Behavioral Economics of Intertemporal Choice with Hyperbolic Discounting

Economics of Asymmetric Information with Signaling Games

Computational Economics with Agent-Based Models for Financial Markets

Ludwig: I love the smell of economic theory in the morning!

Alan: Go ahead and laugh, but it’s not funny. It’s destructive. It doesn’t explain the world as much as it obscures and confuses.

Ludwig: Yes, you do seem confused.

Alan: I’m not as confused as you think I am. And for what it’s worth, the economist’s love of theory and abstraction has infected other disciplines, too.

Ludwig: Such as?

The Wolves of Wall Street

Alan: I know what money is and what it’s supposed to do: to serve as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. I can also grasp the purpose of a savings and loan. I know what a mortgage is. I understand the purpose and function of checks and credit cards.

But what exactly is quantum finance? structured credit trading? esoteric asset-backed securitization? We all rely on a functioning economy, but the people who manage the financial lubricants of commerce — money — have intentionally built a system that has little, if any, relationship with the real world.

Finance has become a stand-alone casino which, when it fails, threatens to destroy not only the gamblers playing inside, but the billions of people standing outside. That’s why Wall Street gets bailed out during a financial crisis, and Main Street does not.

Why have financiers and their friends built a system that privatizes gains and socializes losses? Because it serves their self-interest.

Ludwig: Self-interest is what keeps the economy healthy. It’s what keeps human beings alive.

Alan: Did you know the financial services industry’s share of U.S. GDP has increased from 2.5 percent in 1947 to a peak of 8.3 percent in 2006, and now stands at roughly 7.3 percent? Finance has almost tripled its share of the national economy, even though money has no intrinsic value.

Ludwig: No, I didn’t know those statistics. I’ve been dead for more than 50 years. But the percentages you cite are no surprise given the growing complexity of the global economy. We don’t live in the 16th century. Time moves on. Economies evolve. So does finance.

Alan: You’re missing my point. Complexity isn’t always necessary, although it can be financially profitable… until it collapses under its own weight.

Ludwig: Who are you to decide what is “necessary”? Who appointed you the moral authority about what people need and don’t need? You realize that economics is no longer a branch of moral philosophy, right? Economists no longer wring their hands about the Good. That job has been outsourced to priests, philosophers, and politicians. Economists now worship the god Efficiency — the optimal use of scarce resources to maximize benefits and minimize waste, resulting in the greatest possible output with the given inputs.

Alan: I don’t see efficiency. I see enormous waste and needless complexity, and not just in economics and finance.

“We, the people…”

Alan: When the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1789, how much law did a lawyer need to know? Or a citizen? In 1800, how many law books would you need to study to get up to speed? How much case law surrounded, say, the First Amendment?

Ludwig: Not a whole lot.

Alan: But now you need to attend law school for three years and spend hundreds of thousands of dollars in tuition to join a legal priesthood that has enormous power to shape our lives and our futures. And while “ignorance of the law is no excuse” might have made sense in 1850, it’s meaningless now. Everyone is ignorant of the law, by design. So we’re forced to hire lawyers.

Complexity is not a bug, it’s a profitable feature if you’re a lawyer, a finance bro, the owner of TurboTax… or an economics professor.

Ludwig: All this is consistent with my theory of praxeology, which analyzes human action based on the idea that individuals act purposefully to achieve goals.

Alan: I hate to break it to you, buddy, but that’s not nearly as brilliant and insightful as you think it is. In fact, it’s borderline meaningless. People do things they want to do and, as a result, other things happen. Wow.

Ludwig: Sure, make fun of me, but I’m a famous economist and people still read my books. Who are you?

Alan: Good point.

Tower of Babble

Ludwig: How is all your jabbering about economic complexity relevant to your Substack, anyway? You’ve promised your subscribers content about the future of Jews in the diaspora, yet here you are taking potshots at me, a dead economist.

Alan: Great question! Here’s my answer…

Large, complex systems sow the seeds of their own destruction. My primary example, above, is economics, which began as the study of the production, distribution, consumption, and growth of a nation’s wealth. Now it’s mostly an arcane, mathematical discipline which flourishes in a complex world of pure theory, largely divorced from reality. You guys think you’re economic physicists, and that people are simply atomic particles with credit cards.1 We are not.

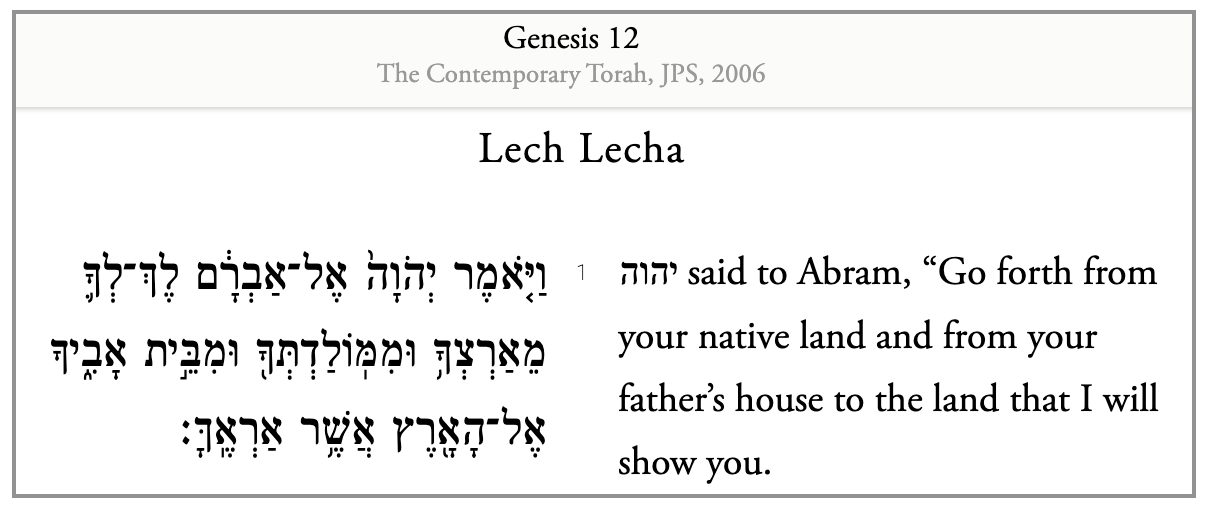

Alan: … What you and your friends have done to economics, we’ve all done to religion. The Story starts simply enough with the best of intentions…

… but sooner than later, the complexity begins. Literature, law, legends, and history begin to accrete, layer upon layer, century after century, until the sediment is so thick we can’t see the foundation anymore. At that moment, someone often steps forward and tries to excavate the site to reveal the Rock upon which we all stand.

There is a wide, substantive, and serious theological gulf between Jews and Christians, but I do believe that Jesus attempted such an excavation. Soon, though, his fresh start and revisions to The Story produced their own institutional, spiritual, and historic sediments. Muslims believe that Muhammed attempted a clear away the detritus once again — the “final” excavation that would, once and for all, reveal the Story’s true essence. Martin Luther also gave it a shot in the 16th century. So did Maimonides, Thomas Aquinas, Moses Mendelssohn, John Locke… and Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, aka the Baal Shem Tov, an 18th-century eastern European Jewish mystic who founded the Hasidic movement, which tried — and still tries — to bring a new, joyful, and accessible spirituality into daily Jewish life by emphasizing a personal connection to God and the sanctity of everyday actions.

Ludwig: You make these religious reboots sound inevitable.

Alan: Nothing is inevitable. We make choices. Complexity is a choice, too, but it’s not the only one available.

Ludwig: Do you have another religious reboot in mind?

Alan: Not a reboot as much as a rediscovery. I think aggadah (Jewish stories, parables, legends, and fables) rather than halacha (Jewish law) has so much to offer us now.

Ludwig: You’re losing me…

Alan: The Bible didn’t begin with Jewish law, it began with a Story: “In the beginning…” I’m less interested in Talmudic debates about the Law, and more interested in discovering threads to the Jewish Story that we might be able to weave together into something more hopeful and life-affirming.

And I’m delighted (and relieved) to report that I am not alone:

Return of the Aggadic Jew

It’s exhilarating (and good for my mental health) when someone else writes what I’ve been thinking for decades.

A few years ago, one of the economics professors at my alma mater (Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut) told me (paraphrased): The discipline of economics is in a crisis. A branch of moral philosophy has been transformed into a mathematical model. Economists looked at what the hard sciences have produced — in short, the modern world — and wanted a piece of the action, so they abandoned moral philosophy, became “economic physicists”… and lost the plot.

Outstanding as always Alan and a great honour to be the subject of an article! I agree with you generally, but the fact remains that if we don’t know the basic basics, we'll be back to socialism.