The temptations of 'deus ex machina'

Second thoughts on Robert McKee's illuminating (and profane) tirade.

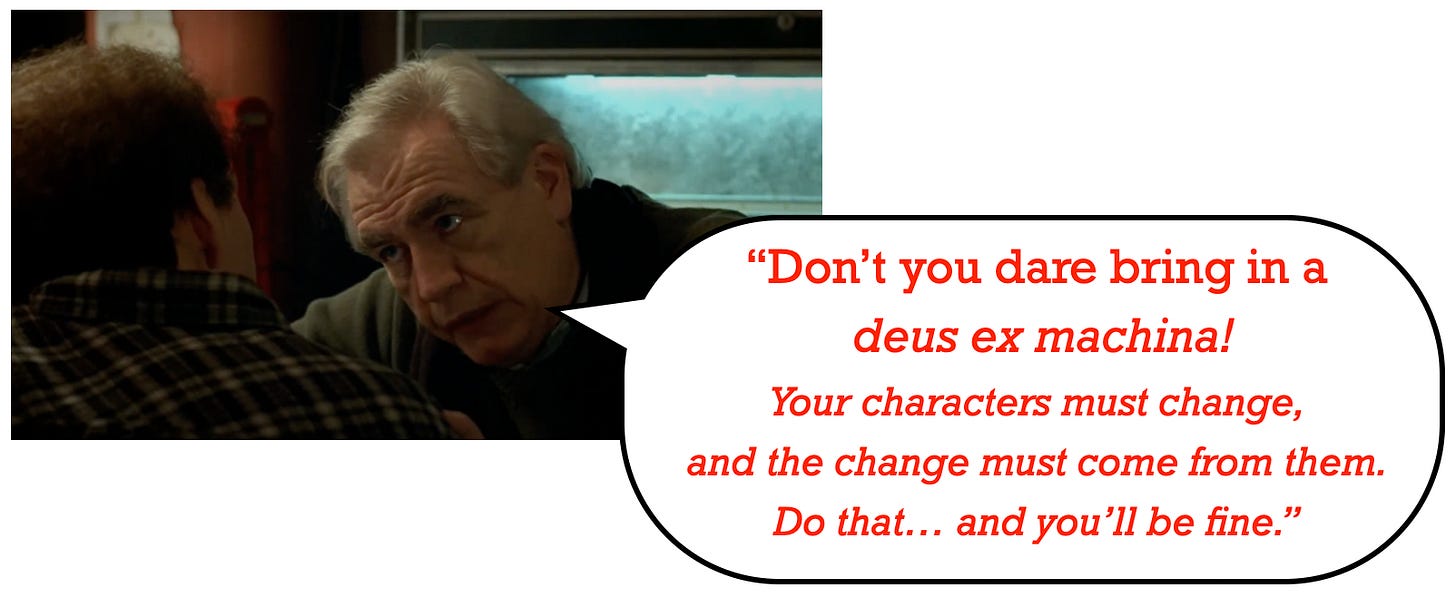

A few months ago, I shared a scene from the movie Adaptation, in which Charlie Kaufman (played by Nic Cage), a screenwriter suffering from a bad case of writer’s block, attends a seminar led by the screenwriting legend Robert McKee (played by Brian Cox).

In the clip (above), Kaufman asks McKee:

“What if a writer is trying to create a story where nothing much happens, where people don’t change, they don’t have any epiphanies, they struggle and are frustrated and nothing is resolved. More a reflection of the real world.”

The question lights a fuse in McKee, who explodes with such profane intensity that I couldn’t help but wonder: What made McKee so angry?

Our “desire for consonance”

Back in July, I offered this explanation, with help from Dara Horn:

Dara Horn continues:

… As a graduate student who was simultaneously writing novels, I read this and patted myself on the back. See, I wasn’t just procrastinating on my dissertation; I was inventing a coherent world! But I very quickly saw the problem. This idea of religion imposing coherence on the world sounded absolutely nothing like the religion I knew best. Kermode’s argument is based on the idea that Western religion is all about “endings.” As he puts it, “The Bible is a familiar model of history. It begins at the beginning with the words ‘In the beginning,’ and it ends with a vision of the end, with the words, ‘Even so, come, Lord Jesus.’” Needless to say, this is not how the Hebrew Bible ends.

Why does this bit of literary theory explain Robert McKee’s profane rant?

Because Kaufman is asking an extraordinarily provocative question, which I’d rephrase like this:

What if real life doesn’t fit the narrative template that you, Mr. McKee, have taught thousands of aspiring screenwriters for decades — dramatic stories with beginnings, middles, and endings? What if real life doesn’t satisfy what Frank Kermode calls our “desire for consonance”? What if the real world is more like the Jewish Story than the Christian one?

Screenwriters and Christians share this “desire for consonance,” which explains why McKee erupted in response to Kaufman’s (rather Jewish) question.

At least that’s what I believed back in June. But I was wrong.

Last week, I stumbled on the follow-up scene from Adaptation, which I had forgotten:

“Don’t you dare bring in a deus ex machina,” says McKee.

Meaning: Don’t resolve your story’s dramatic tensions with an act of god. Instead, your characters must find a way to solve their problems without divine intervention.

Amid the ruins (circa 135 CE)

Imagine, for a moment, that we’ve traveled back in time almost 2,000 years to the city of Jerusalem. The Roman legions have crushed another Jewish revolt and destroyed the Second Temple. Dead bodies fill the streets, and the Jews who have survived are packing their bags and leaving town. The second Jewish exile has begun.

When seen through a storyteller’s lens, this narrative — which began with the first line of Genesis and has now arrived at this disastrous juncture — is a mess. The Jews’ sovereignty in the Promised Land has come to a catastrophic end (again). Jewish hopes and dreams for the redemption of both Israel and the world seem to have vanished (again).

Bloodied and beaten by the overwhelming power of Rome, what should this Jewish remnant do next?

At a secret encampment in the hills outside of Jerusalem, a group of Jewish leaders convene to evaluate their options:

Let’s re-arm and keep fighting, says Judah. We can still defeat Rome… G*d willing.

Let’s rebuild the Temple somewhere else, somewhere safer, says Aaron. We must fulfill all the Commandments, including the ritual of animal sacrifice.

I hear the Yukon is empty and available, says

. Or maybe we should go to Uganda.Let’s abandon our covenant, our faith, our culture, our land, and our dead-end Story, says Kevin. We should pledge our loyalty to Caesar and submit to Rome’s overwhelming power. Because if you can’t beat ‘em…

Let’s revive the playbook from our Babylonian exile, says Ezra. Our Book should be the center of Jewish life, not the Temple. Our communal narrative begins with “In the beginning…” and soon we’re walking with Abraham and Sarah into an uncertain future (Lech Lecha). Generations later, we follow Moses out of Egypt… we stand together at Sinai… we wander in the wilderness… we conquer the land… we’re exiled… we immerse ourselves in the Book… we evolve (slowly) as a people… the Prophets shake us from our spiritual slumber… and on we go through history until we reach this painful moment. The Story must come first because it’s the only way we can keep hope alive.

These options fuel a heated debate among the leadership, but they cannot agree on the next step. Deadlocked, these Jewish exiles have no vision or hope. Just as they are ready to give up and disband, a guy named Paul stands up and offers a radical alternative:

Do you all remember the preacher they called Jesus? asked Paul. That young charismatic rabbi who healed the sick… who comforted the widow, the orphan, and the stranger… who flipped over the moneychangers’ tables… and who was then crucified by the Romans? Remember that guy?

What if He was and is our long-awaited Messiah? What if He is the fulfillment of The Promise? What if G*d destroyed the Temple because He was sick and tired of our hollow rituals, so He came to walk among us in the flesh? What if Christ’s crucifixion — his substitutionary atonement — washes away our sins, once and for all, so that we no longer need to sacrifice animals or anything else in the Temple? What if our Jewish Story has been divinely blessed with a new beginning?

[… Long, pregnant pause. Complete silence. Paul goes on…]

What if Christ resolves all the tensions and contradictions within our Jewish Story? What if we leave behind the Old Covenant and are born again into a New One (which I’ve outlined in a New Testament)? What if G*d became a Perfect Man who appeared on the stage of human history to solve all our problems, absolve us of sin, and show us The Way?

For a few seconds, no one says a word. Then, in the back row, a man stands up, snuffs out his cigarette, and slowly makes his way to the front of the room.

Who is this stranger? Oh my goodness… it’s Robert McKee! The legendary screenwriter has apparently traveled back in time to share his storytelling wisdom with us!

McKee walks up to Paul, puts a hand on his shoulder, leans forward, and says:

Rabbi Robert McKee

So I got it wrong.

When confronted with Charlie Kaufman’s question, McKee didn’t yell because he couldn’t bear contemplating life without “consonance.” Rather, McKee yelled because he refused to concede that “nothing much happens” in life and that “nothing is resolved” — even when McKee is uncertain what that ultimate resolution should be.

Or as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel might have told Charlie Kaufman: “Remember that there is meaning beyond absurdity.”

McKee’s tirade is a challenge. He wants Kaufman (and us) to assemble the discrete and seemingly pointless moments in life and transform them into a coherent and meaningful narrative. But according to McKee’s storytelling commandments, no god or gods can suddenly intervene to fix what we have broken.

No deus ex machina.

No one is coming to save us. Whatever happens next is on us.

But here’s the good news: We are not the first cowboys at this rodeo. A lot of productive work was done before we arrived on the scene, so we don’t have to start a new Story from scratch. We don’t need a new Year Zero.

Instead, we can build on the stories we’ve inherited, stories that have stood the test of time. Then, when we’re familiar with the characters, the plot, and the drama thus far, we can add the next chapter, which might help steer our Story in a better direction… if we’re lucky.

Isaac & Ishmael, Moses & Aaron… Julius & Philip

At the end of their conversation at the bar, Robert McKee sends Charlie Kaufman back home to work out Act III of his screenplay in solitude. Whatever happens in the end, it’s all up to Charlie.

As we struggle to find a way to resolve the rising tensions and contradictions of the present moment, we enjoy an enormous advantage — a narrative superpower that Charlie Kaufman didn’t possess.

We are not alone.