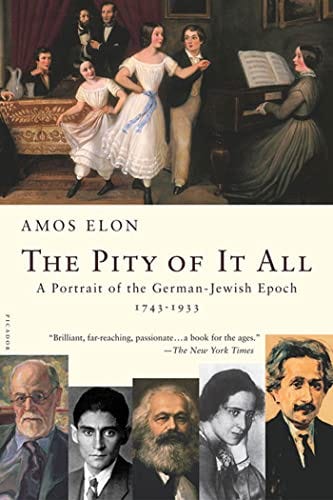

The Pity of It All

Normalcy bias and the danger of communal delusions

Jessica Wildfire, who writes OK Doomer on Substack, recently posted a fascinating essay titled “It’s Not Cool to Overreact: How Normalcy Bias Will Define Our Future.”

What, you ask, is normalcy bias? Simply put, it’s a cognitive inclination that leads people to minimize or ignore evidence-based warnings that a disaster is imminent. For example, the scientific consensus says climate change is real and caused by human activity, but a lot of people still say Nahhhh. I don’t believe it.

Two passages in Wildfire’s essay caught my eye:

“Large groups of people facing death act in surprising ways. Most of us become incredibly docile… Usually, we form groups and move slowly, as if sleepwalking in a nightmare.” In short, we don’t panic. We chill way out.

“We are sensitive to the perception of others viewing us as abnormal. Within social relationships, very few want to be seen as alarmist, overreactive or a fool because if they are wrong about a threat then they will be regarded as less credible in the future.” … It’s not cool to overreact.

“Everything is fine. We’re going to be okay.”

This book, which I read almost 20 years ago, still gives me the chills. It’s also a soul-crushing example of the dangers of normalcy bias.

The promise of the Enlightenment

The Pity of It All begins in 1743 when 14-year-old Moses Mendelssohn walks through Berlin’s Rosenthaler Tor, “the only gate in the city wall through which Jews (and cattle) were allowed to pass.”

A promising Talmudic scholar, Mendelssohn would eventually become one of the leading voices of the Jewish Enlightenment. “Mendelssohn’s great ambition,” Elon writes, “was to end the age-old social and intellectual isolation of Judaism, some of which had become self-imposed.”

For many German Jews, the (Jewish) Enlightenment was an irresistible invitation: Join the family of Man! Embrace this promising New Age, animated by Reason — facts, evidence, and science —and unencumbered by tradition, spirituality, and revealed Truth. Leave behind what makes you different, and embrace what makes us all human. The train of progress is finally here. All aboard!

From Amos Elon’s introduction:

One of the first practicing Jews to be fully assimilated into high German culture, Mendelssohn became the first German Jew to achieve European prominence as a philosopher and a man of letters, admired by Kant and Herder and by beaux esprits everywhere…. His contemporaries hailed him extravagantly…. For his achievements as a philosopher and religious reformer, he was acclaimed as the “German Socrates” and the “Jewish Luther.” For his advocacy of an enlightened secular state, the French philosophe Mirabeau placed him on the same pedestal as the authors of the United States Constitution.

Throughout the nineteenth century, German Jews celebrated, idealized, and drew hope from Mendelssohn’s famous interreligious friendships. … Mendelssohn became their patron saint, a model for all who sought to preserve their ethnic or religious identity but share in the general culture.

The book concludes in 1933. You know what happens next.

“The call is coming from inside the house…”

The Pity of It All is surprising not because of the looming disaster (which you already know is coming). It’s surprising — and painful — because many German Jews refused to acknowledge the danger they were in, despite the evidence. Just a few years before Hitler came to power, too many Jews were still in deep denial.

In the 1930 elections, Nazi representation in the Reichstag increased nearly tenfold to 107 deputies… First reactions to the Nazi upsurge were mixed. Many Jews saw it as a temporary warp in what was, after all, a civilized country. Einstein remained calm. The Nazis’ strong showing, he claimed, resulted from the “momentary economic slump” — it was a little more than a childhood disease of the young republic. … Ernst Feder’s confidants in the government assured him that there was no reason to worry — Hitler, Goebbels, and their henchmen weren’t dangerous. They would never come to power. [Feder, a Jewish lawyer and journalist, was an ardent supporter of post-imperial democratic Germany.] … Otto Meissner, Hindenburg's chief of staff, assured Feder that Hindenburg was a man of extraordinary decency and personal integrity who had sworn loyalty to the republic. Even if the Nazis gained a majority, the president would never confirm Hitler as chancellor.

In 1933, President Hindenburg confirmed Hitler as chancellor.

![First grade pupils, both Jewish and non-Jewish, study in a classroom in a public school in Hamburg. [LCID: 38317] First grade pupils, both Jewish and non-Jewish, study in a classroom in a public school in Hamburg. [LCID: 38317]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8AR0!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8bf40483-65bb-4927-9d34-e3548c90491b_1024x722.jpeg)

The moment [early 1930s] was one of paradox, of surging Nazism and increasing assimilation, of anti-Semitic outrages and growing prominence for Jews in every field of Weimar culture. Max Liebermann was president of the Prussian Academy of Arts. Max Reinhardt, showered with honorary doctorates from the universities of Kiel, Frankfurt, and Tübingen, was directing Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Christian morality play Everyman on the steps of Salzburg’s cathedral. Jews mistook such prominence as an index of their successful integration. The few who suspected otherwise must have repressed their concerns.

In other words: Normalcy bias.

The Story We Live By

We can tell ourselves a story that we are children of the Enlightenment who wield the power of Reason to help us see and speak the truth, and build a better world.

We can tell ourselves that the American story — about human rights, liberty, progress, and the dignity of the individual — is the “last, best hope of Earth.”

We can tell ourselves a story that we live in a civilized country — a beacon of diversity, tolerance, and freedom — so It Can’t Happen Here.

We tell ourselves all sorts of stories. And they can change in a heartbeat.

All true. But equally true is that stories are essential to give us meaning. Quite the paradox. (ps I didn’t receive your article by email. Am I on the list?)