“Put the Jews on the moon”

What prompted Joseph Campbell's tasteless little joke?

Joseph Campbell (1904-1987), a professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College whose work focused on comparative mythology and religion, first appeared on my radar — and everyone else’s, it seemed — in the late 1980s when Bill Moyers produced the wildly popular PBS documentary series, The Power of Myth.

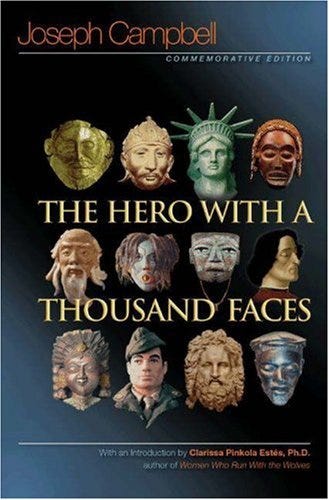

Campbell was the star of the series, which illuminated and popularized his theory of the monomyth, a singular template that described the universal structure of mythological narratives. In The Hero With A Thousand Faces (first published in 1949), Campbell calls his monomyth The Hero’s Adventure, in which…

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

Campbell’s template has become widely influential among storytellers, including filmmakers such as George Lucas (Star Wars), who credited Campbell with helping to shape the adventures of Luke Skywalker, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Darth Vader, and friends.

Every joke has a grain of truth

One tiny footnote to Campbell’s legacy is immensely revealing. It appeared in “The Faces of Joseph Campbell,” by Brendan Gill (The New York Review of Books, September 28, 1989).

In short: Gill accused Campbell of being an anti-Semite and a racist. Many people rushed to Campbell’s defense, sparking an extended back-and-forth in the pages of the NYRB, The New York Times, and elsewhere. One flash point was the meaning of this anecdote (as described in the NYT):

When the astronauts landed on the moon, Mr. Gill writes, illustrating what he alleges to be Campbell's private anti-Semitism, “Joe made the repellent jest” that “the moon would be a good place to put the Jews.” Mr. Gill says the remark was heard by a member of his family who was a student at Sarah Lawrence.

The charge of anti-Semitism does not interest me at all. But the joke about sending Jews to the moon — that is worth exploring.

Why did Campbell want to put the Jews on the moon instead of, say, Black people? Or Asians? Or Mexicans? Or redheads? Or Rastafarians?

What is Campbell’s joke really about?

Here’s my theory:

Imagine you’ve just developed a new idea. It’s a big idea about how all the world’s mythic narratives have the same essential structure. It’s a Theory of Everything for stories, a Holy Grail for narratologists and mythologists. And it could be your ticket to fame and fortune.

You published a book that explains it all in 1949, but twenty years later when Neil Armstrong becomes the first man to walk on the moon, your big idea still hasn’t found an audience. (Your best-selling books, your hit PBS series, and your creative impact on Hollywood big shots are all still decades away.) Hungry for critical approval and popular acclaim, you wonder why you’re still laboring in relative obscurity. But the truth is, you already know the answer: There’s a major flaw in your big idea — a glaring exception to the Hero’s Journey template.

It’s the Jewish Story (and by extension, the Christian and Muslim stories, too). The Hebrew Bible and all that follows seem to break the mold of the monomyth.

But wait, I hear you saying, what about Moses? His story maps perfectly onto the Hero’s Journey template:

The stories of Abraham and Joseph follow a similar arc, as do countless other Biblical figures. But those individuals represent the mini-myths or the sub-plots of the Jewish Story, writ large. Each one of them is a chapter in a much bigger master narrative that has — and this is the key point — evolved into a real-life drama that is not yet complete.

The people who tell this Story and then live inside it — the Jews — are still here. And unlike the ancient Greeks, Romans, Persians, Assyrians, Babylonians, and Egyptians (who all had heroic myths of their own), the Jews haven’t disappeared. They’re still here on the stage of history, telling their Story every year on Passover, while trying, in real-time, to cobble together a sensible and humane next chapter.

Put another way: the ancient Jewish myths that emerged from the mists of antiquity eventually became the narrative keystone for real, documented history and current events — seamlessly extending an old Story while capturing the imagination and animating the lives of roughly four billion Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

The Bible has begotten some heroic moments, of course. But Abraham, Sarah and Hagar, Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, and the rest of this very extended family — they speak to us because they’re all too human. We recognize their struggles, hopes, and dreams as our own. We know these people. They are us.

As a result, the Bible is a myth unlike any other — one that does not follow the narrative roadmap revealed to us by Joseph Campbell. And unlike the millions of Campbell acolytes who dream about embarking on an heroic adventure of their own design, the children of Abraham know that their communal adventure began long ago; that each one of us today is blessed with a unique and essential role to play; and that the next generation will keep this Story — and the eternal Hope it embodies — alive.

No wonder Joseph Campbell wanted to send the Jews to the moon.

Postscript