“That was the takeaway. When the social and political barometric pressure begins to drop, when you can feel that tingling: Leave.”

From “Living Through the Beginning of the End,” by Gal Beckerman. The Atlantic, December 19, 2022:

In The Oppermanns, the members of one German Jewish family come to realize, each at a different pace, that they are no longer welcome in the country they have come to think of as home. Showing us this dawning, its varying velocity and consequences, is Feuchtwanger’s project. The best-selling writer of popular historical fiction was already living in exile in the south of France by the spring of 1933, when he began writing this book. The Nazis had ransacked his personal library. His own work was being burned in massive bonfires. And his German citizenship had been stripped. It was at this moment that he cast back just a few months to begin his story of the Oppermann siblings, describing their fate over the course of nearly a year, from November of 1932, just before Hitler was appointed chancellor, through his quick consolidation of all power, and ending in the summer of 1933 with the family “scattered to all the eight winds.” …

Feuchtwanger ratchets up the moral intensity for Martin’s 17-year-old son, Berthold. A Nazi has recently become his instructor and informed him that the report the young man had been planning to deliver to the class—“Humanism and the Twentieth Century”—won’t do. The Nazi forbids him “on principle” from taking on such “abstract subjects.” Instead, he switches Berthold’s topic to Arminius, an ancient tribal leader who triumphed in battle over the Romans and is heralded as a proto-German nationalist. From “Humanism” to “What can we learn today from Arminius the German?”: Feuchtwanger here, as in many other places, is far from subtle.

Berthold’s talk goes awry when he begins to raise a few possible objections as to Arminius’s lasting significance. From the back of the classroom, the glowering Nazi instructor starts shouting, “Who do you think you are, young man? What sort of people do you suppose you have sitting here before you? Here, in the presence of Germans, in this time of German need, you dare to characterize the tremendous act that stands at the beginning of German history as useless and devoid of meaning?” To this harangue, Berthold answers, “I am a good German, Herr Senior Master. I am as good a German as you are.” A battle of wills ensues, with the Nazi demanding a public apology from Berthold if he wants to avoid expulsion, and Berthold, like his father, standing on principle, defending his dignity.

Berthold can’t understand what he did wrong. He fails to see that national identity and power matter more than intellectual inquiry in Nazi Germany. The greatest injury to his sense of dignity is the notion that he must lie. Or, more precisely, that he must take back something he said in his lecture that was irrefutably true—that Arminius’s resistance to the Roman legions, the source of the nationalists’ pride, made hardly a dent on the empire. The primacy of lying, its role as the building block for this new form of German-ness, is something that he, and the other Oppermanns, simply can’t handle. “Was it un-German to tell the truth?” he asks himself. …

But what pulses through this story of the Oppermanns is the emotion. Feuchtwanger, sitting in exile, was grieving and angry. He was panicked. Not enough people were seeing just how corrosive this confusion of truth and lies could be, how harmful it was for the most vulnerable in society, who were liable to be turned into scapegoats for almost anything. …

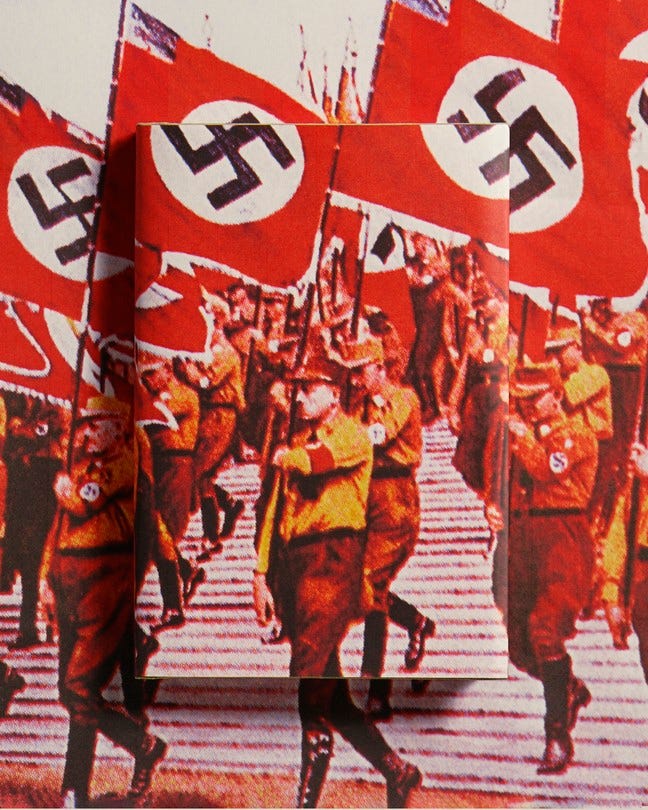

One by one, each sibling is confronted with a reality that feels as determined as a natural disaster, in which the volume of lies being hurled against them, and against Jews in general, becomes impossible to even begin to refute. “It was an earthquake, one of those great upheavals of concentrated, fathomless, worldwide stupidity,” Feuchtwanger writes at the moment of no return. “Pitted against such an elemental force, the strength and wisdom of the individual was useless.” …

For all the lessons he is trying to impart in 1933, there is no clearer answer about when exactly it’s time to go, when holding on to dignity becomes self-indulgent and dangerous. What remains instead is a deep sense of that rumbling “elemental force,” and the impossible choices should you find yourself stuck in its path.